Yunnan Baiyao Research

Posted by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Director, Institute for Traditional Medicine on Nov 22nd 2022

YUNNAN PAIYAO

Uses for injury and surgery; gastro-intestinal, respiratory, and urogenital disorders

by Subhuti Dharmananda, Ph.D., Director, Institute for Traditional Medicine, Portland, Oregon

Yunnan Paiyao (literally, the white herbal medicine from the province of Yunnan) is the most famous of the patent remedies in China. It has a gleaming reputation for ability to stop bleeding, whether caused by injury or ailment, and it has been tried, with reported success, for the treatment of a number of other conditions as well. It is taken internally and/or applied topically. The correct pinyin spelling of the name of this product is Yunnan Baiyao, but the package label has long had it spelled by the earlier Wade-Giles system; it is the spelling that is chosen for use in this article.

HISTORY

Yunnan Paiyao was devised by Qu Huanzhang, a Chinese physician of Yunnan, in 1916 (1). It has been claimed that the original formulation was altered somewhat during the cultural revolution when the factory owners were forced to yield their proprietary control and reveal the ingredients (2). Regular larger-scale manufacture of the product began around 1956 at the Yunnan Paiyao Factory, which was expanded in 1971. There are reports that North Vietnamese soldiers were found carrying Yunnan Paiyao as a battlefield remedy for wounds during the 1970’s (3). The initial Chinese research on Yunnan Pai Yao began in the early 1980s.

During a visit I made to China in 1983, our team asked several Chinese experts about patent medicines, inquiring as to what was deemed the best one: Yunnan Paiyao was well-known and highly respected, receiving the characteristic thumbs-up approval. The product gained the interest of physicians in Chinese hospitals and several medical research facilities; its use in these settings continues to the present. The heightened interest in this product was illustrated by review articles appearing in a Yunnan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine (4) and in the Bulletin of Chinese Materia Medica (5) in 1986, listing dozens of applications. The factory began preparation of several additional easy-to-use forms at that time.

PREPARATIONS

Yunnan Paiyao was traditionally provided in small bottles with 4 grams of powder, intended for topical use or for mixing with other ingredients. Each bottle is accompanied by a small red pill, called Bao Xian Zi and commonly known as the “safety pill.” It is to be taken 1 pill per day, intended for treating shock due to significant hemorrhage; it may also help alleviate pain. Its ingredients are not revealed. Although some physicians (15) have made use of this pill as a single remedy for certain disorders (angina pectoris, pyogenic infections, epitasis) and claimed that the effects were similar to that of Yunnan Paiyao, the usual procedure is to take the pill along with the first dose of Yunnan Paiyao if there is severe bleeding; but for less severe bleeding, the pill is not used. Other forms of Yunnan Paiyao are:

- Capsules containing 250 mg: usually taken in doses of 2 capsules each time, two to four times daily (a sheet of 16 blister-packed capsules has 4 grams of the powder, sufficient for a 2–4 day supply, which is usually the intended course of therapy). Each strip of 16 capsules is accompanied by one safety pill.

- Small bottles (30 cc) of liquor (alcohol extract of the powder): the oral dose is 3–5 cc each time, 3–5 times per day, for a total dosage of 15 cc/day, so that one bottle is a two day supply. The liquor can easily be applied topically; the package label recommends rubbing it in forcefully for several minutes.

- Yunnan Paiyao plaster: for easy retention of the herbs against the skin. Each carton contains 20 boxes, with 5 plasters per box. The plasters are very thin and measure about 2x4 inches. Once applied, they last for about four hours, after which time the aromatic constituents are nearly gone. The adhesive, which covers the whole plaster, sticks tightly to body hair, as will be noted during removal.

INGREDIENTS

The Yunnan Paiyao formulation remains obscure, though certain ingredients are said to be reliably established. The herb sanqi (Panax notoginseng) is a product of Yunnan Province used for stopping bleeding and is believed by many Chinese commentators to be the principal anti-hemorrhage component of the product. Chemical analysis of the Yunnan Paiyao powder has revealed some saponins, possibly those found in Panax notoginseng (however, see appendix for a possible alternative herb material also named sanqi). Geranium (laoguancao) is also identified as a standard ingredient. Two aromatics, borneol and musk, traditionally used together, are evident in the taste and smell of Yunnan Paiyao. The factory may get its borneol from Blumea balsamifera, which grows in Yunnan. Borneol is said to “open orifices, move qi, move blood, remove swelling, and control pain (10).” True musk is obtained from the dried sexual secretion of the musk deer, a native of Yunnan and nearby provinces (Sichuan and Tibet). It is now always substituted by the main active constituent, muscone (also used by the fragrance industry), in patent remedies. Musk is said to “open orifices, invigorate blood circulation, induce parturition, and promote meridian circulation.” Muscone has the same effects. Borneol and musk do not stop bleeding, but treat blood stasis and pain. Additional information about ingredients is in the appendix. It has been suggested recently that the stop-bleeding action of the product may be due to the presence of microscopic plant fibers (nanofibers) that stimulate platelets to aggregate (28), thus explaining how a low dosage of herb material, for which chemical constituents are present in small amounts, might have such dramatic effect.

DURATION OF THERAPY

In many cases, Yunnan Paiyao is used for only 2–4 days; however, some of the applications are for disorders that may require several days of treatment. Generally, Yunnan Paiyao is not intended to be used regularly for more than about 15 days. If the disorder being treated is not resolved adequately in that time, one should probably try a different remedy. In cases of severe injuries, one can switch to using raw tien-chi ginseng (Panax notoginseng) tablets or a formulation based on this herb for continued therapy once healing has progressed.

It has not been clearly established that longer duration therapy with Yunnan Paiyao might be harmful in any way, but it is rarely used. In one report (16), a Japanese practitioner administered to patients a high dose of 16 capsules per day (4 grams) for 10–20 days, and then reduced the dosage in half, and treated for about 5–10 weeks at that dosage (this was for one case each of osteomyelitis, leukemia, and stomach cancer; other herbs were also given to the patients). The author of Anticancer Medicinal Herbs (8) says that the “People’s Hospital in Fuzhou City tried to cure cancer of the esophagus and liver with Yunnan Paiyao. They asked the patients to take the powder after meals, three times a day, each time 1 to 2 grams. Each course constituted two weeks and between courses, the powder was ceased for one week. The drug was administered on a long term basis.” Note that in this case, long term administration was accomplished by taking a 7 day break after each 14 day period of administration. Yunnan Paiyao is usually applied topically for a duration similar to that for the internal remedy: up to 15 days. There is one report of using Yunnan Paiyao topically for two months for tubercular ulceration (17).

MEDICAL APPLICATIONS

The most general use of Yunnan Paiyao is to treat bleeding, used by oral administration in the dosages described above. The powder is sometimes applied to a narrow open bleeding wound in an attempt to “lacquer” the edges together (one must be able to hold together the edges of the wound long enough that the blood does not wash away the applied powder). Examples of suggested uses in internal medicine include bleeding of the gastrointestinal system (stomach ulcer, stomach cancer, ulcerative colitis) and of the respiratory system (tuberculosis, bronchiectasis, lung cancer, nose bleeds, chronic sinus inflammation). The product is also claimed to promote normal blood circulation, reduce inflammation and swelling, and alleviate pain. It is suggested for menstrual disorders such as dysmenorrhea, amenorrhea, or excessive menstrual bleeding.

When taking Yunnan Paiyao internally, it is usually recommended that it be taken with warm water to treat hemorrhage and with wine to treat blood stasis (27). Today, the powder is mainly given in capsules. When applying Yunnan Paiyao powder topically, if the surface to be treated is not moist (e.g., open injury), the powder is mixed with wine or other alcohol, or with water, or with Vaseline or similar medium to produce a paste; the powder or paste is held in place with a plaster or taped gauze.

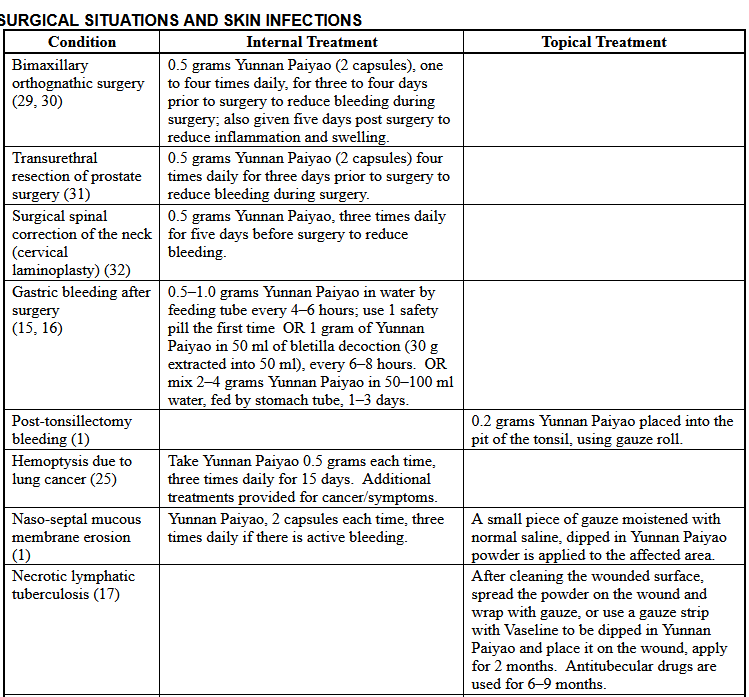

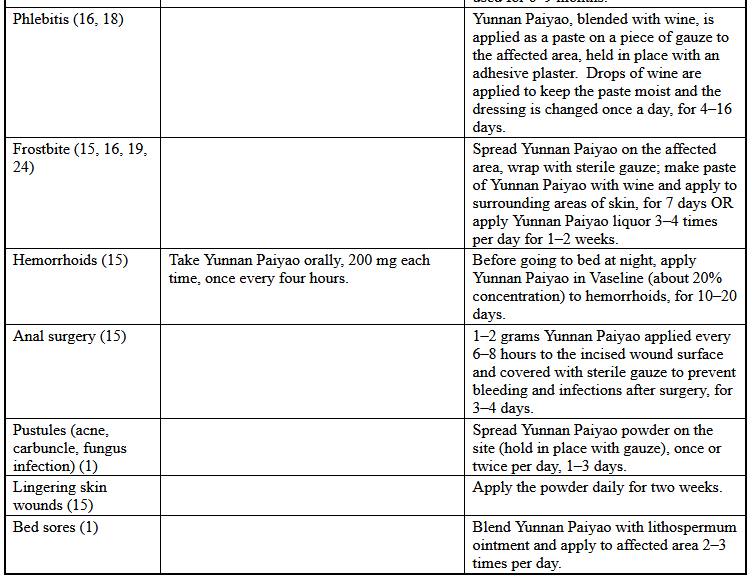

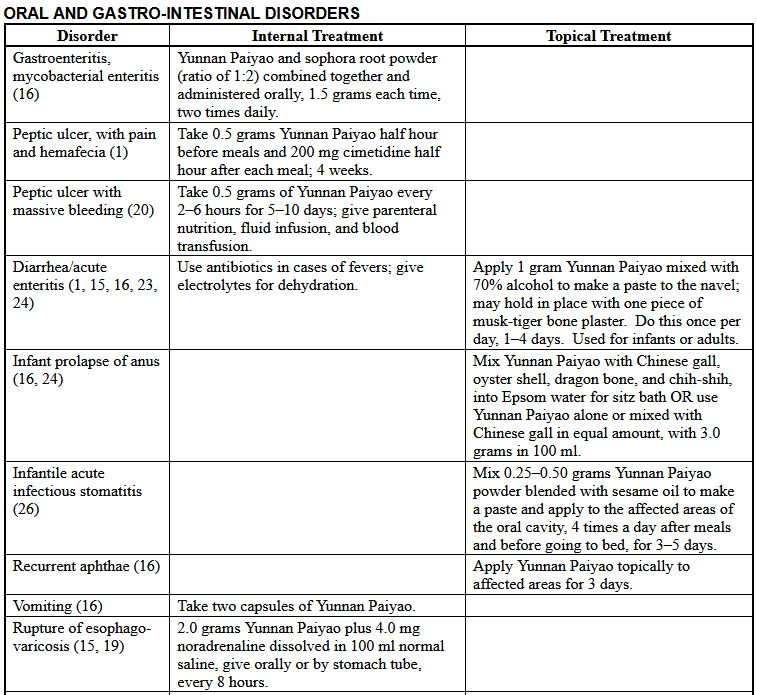

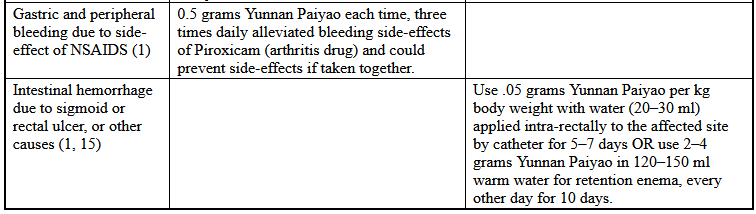

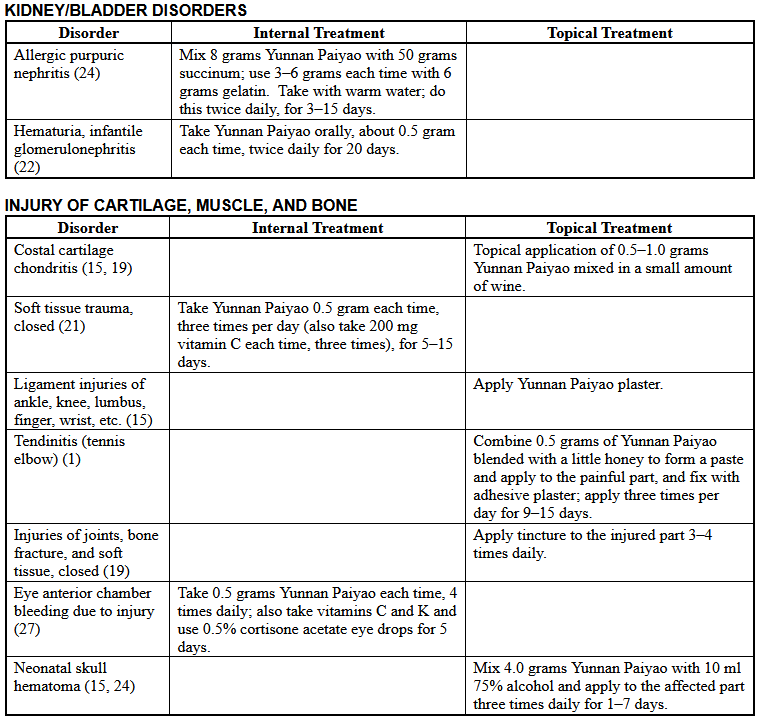

So many diseases have been reportedly improved by Yunnan Paiyao that only a few selected items are listed below. The following representative means of using the powder (or other common preparations) are from several literature reviews and individual clinical reports, divided according to application. For each condition being treated, the use of Yunnan Paiyao was reported to be highly effective, so no effort was made here to give specific reported results. This section reveals some of the different methods of applying the compound and should guide practitioners in considering its use for similar, but unlisted, applications. When a treatment method is described in both the internal and topical categories, it means that the two methods were used together. Where there are several references given to treatment of a specific ailment, this is usually because the original clinical report was presented in several review articles; if there are differing treatments, they are listed and separated by “OR.”

CAUTIONS

The following cautions about using Yunnan Paiyao have been raised:

- A few people are allergic to one or more of its ingredients. Therefore, one should immediately discontinue use if any signs of allergy reaction occur. In a very small number of cases, it was reported that allergic shock (anaphylaxis) occurred (14). Skin allergy reactions are more frequent when the powder is applied to a large area of skin; it is evident in some cases of using the plaster (in one report, it occurred in 4% of those using the plaster, and might involve the “glue”). Borneol may be responsible for some of the allergy reactions reported to Yunnan Paiyao.

- When applying to an open wound, make sure that steps are taken to prevent infection. Bacteria can become trapped in the wound area when it is sealed up by the drying blood and Yunnan Paiyao powder.

- In most cases, do not exceed the recommended daily dosage of 2.0 grams per day for adults; however, there are reports of using 4.0 grams per day without adverse effect. Do not consume more than 2.0 grams for a single dosage. If used with children, the dosage for internal use must be reduced accordingly. As an example: in a report on treatment of urticaria (15), adults were given 0.5 grams each time, three times daily; children aged 10–15 were given 0.33 grams each time (2/3 the adult dosage), and children under age 9 were given 0.25 grams each time (1/2 the adult dosage. In several reports in which infants were treated, Yunnan Paiyao was applied topically, not swallowed. When given orally to patients 4–11 years old for nephritis (22), children were given 35–70 mg/kg/day, with the average amount of 50 mg/kg/day (a 20 kg child, 44 pounds, would receive about 1.0 grams of Yunnan Paiyao per day, divided into two equal doses (2 capsules each time).

- The manufacturers suggest that the effects of the product will be diminished if one consumes the following foods within 24 hours of oral administration: broad beans, fish, sour or cold food. Although sour food is said to be contraindicated, several clinical reports indicated use of vitamin C with Yunnan Paiyao. By “cold foods,” it is meant foods with significant cooling action in the traditional sense (China did not have refrigeration available until recently). The indicated foods are traditionally thought to contribute to accumulation and stasis in cases of injury or disease.

- Be careful when swallowing the loose powder that it is not accidentally aspirated, as this can cause choking cough and congestion.

- Pregnant women should not take this remedy.

- The “safety pill” should not be taken in doses of more than 1 per day. Excessive use can cause bleeding.

HOW EFFECTIVE IS YUNNAN PAIYAO?

The clinical testing of Yunnan Paiyao, mainly reported during the period 1986–1995, confirms that Yunnan Paiyao is a valuable remedy, especially for injuries, surgical disorders (problems that are usually treated by surgical means), gastro-intestinal disorders, respiratory, and urogenital disorders. Recent research at Peking University confirms its value for surgical applications, showing that a few days administration of Yunnan Paiyao before surgery reduced bleeding during and immediately after surgery by about one-third, and when given for a few days after surgery reduced swelling significantly (29-32). In these studies, allergic reactions did not occur, nor was there any formation of clots outside the surgical site. Some of the Chinese literature suggests that in cases of severe bleeding, when other methods have failed to have effect, Yunnan Paiyao is resorted to as the emergency remedy. It also appears to be a common personal remedy for bleeding associated with injuries.

For Western practitioners, Yunnan Paiyao is particularly attractive because of the convenient encapsulated form and the relative low cost, in contrast to decoctions commonly listed in the Chinese medical literature. Similarly, the powder, liquor (tincture), and plaster make topical application quite easy compared to many suggestions for other topical therapies found in the Chinese herbal literature.

REFERENCES

- Lu Xinhua and Liu Fangan, “New progress on clinical applications of Yunnan Baiyao,” Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1993; (3): 17–18.

- Fruehauf H, personal communication, 12/97.

- Chun-Han Zhu, Clinical Handbook of Chinese Prepared Medicines, 1989 Paradigm Publications, Brookline, MA.

- Shen Haiming, “Clinical uses of Yunnan Baiyao in the last thirty years,” Yunnan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1986; 7(4): 46–49.

- Yang Tong, et al., “Uses of Yunnan Paiyao,” Bulletin of Chinese Materia Medica, 1986; 11(2): 47–50.

- Smith FP and Stuart GA, Chinese Medicinal Herbs, 1973 Georgetown Press, San Francisco, CA.

- Dharmananda S, “The jin bu huan story,” 1994 START Group Manuscripts, ITM, Inc., Portland, OR.

- Chang Minyi, Anticancer Medicinal Herbs, 1992 Hunan Science and Technology Publishing House, Changsha.

- Anonymous, Zhongguo Bencao Tulu (Illustrated Guide to Chinese Materia Medica), 1988 Commercial Press, Hong Kong

- Perry LM, Medicinal Plants of East and Southeast Asia, 1980 MIT Press, Cambridge, MA.

- Hong-Yen Hsu, et. al., Oriental Materia Medica: A Concise Guide, 1986 Oriental Healing Arts Institute, Long Beach, CA.

- Shiu-ying Hu, An Enumeration of Chinese Materia Medica, 1980 The Chinese University Press, Hong Kong.

- Zhao Guo-qiang and Wang Xiu-xun, “Dencichine, the hemostatic constituent of Panax notoginseng,” Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs, 1986; 17(6); 274–275, 260.

- Hu Mingcan and Jiang Keming, “A probe into the ill effects of Yunnan Baiyao,” Chinese Patent Drugs, 1989; 11(1): 36.

- Xing Yamin, “New Progress on clinical applications of Yunnan Baiyao,” Information on TCM 1990; (1): 11–13.

- Mei Quanxi, “Extended uses of Yunnan Baiyao,” Chinese Patent Drugs. 1990; 12(1): 20–21.

- Wang Benyu and Zhang Qiaomin, “A learning of applying Yunnan Baiyao to treat necrotic lymphatic tuberculosis,” Practical Journal of Integrating Chinese with Modern Medicine, 1995; 8(10): 582.

- Zhou Shijie and Lu Songfen, “Yunnan Baiyao in treating transfusion phlebitis,” Chinese Journal of Chinese Materia Medica, 1994; 19(7): 438.

- Hou Lianbing, et al., “Clinical applications ofYunnan Baiyao novel preparation,” Chinese Patent Drugs, 1993; 15(4): 22–23.

- Zhao Shu-ying, et al., “Treatment of massive bleeding of peptic ulcer by integrated Chinese and Western medicine,” Beijing Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1985; (4): 27.

- Chen Shaoli and Wu Yong, “240 cases of closed soft tissue trauma treated with Yunnan Baiyao,” Middle Journal of Medicine, 1995; 30(11): 54.

- Gao Yinhuai, Gao Yinnan, and Diao Junli, “Clinical observation on Yunnan Baiyao in treating infantile acute glomerulonephritis hematuria,” Jiangxi Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1996; 27(1): 38.

- Yu Huidong and Han Yanping, “Investigation on curative effect of Yunnan Baiyao in treating infantile autumn diarrhea by navel-application method,” Practical Journal of Integrating Chinese with Modern Medicine, 1996; 9(2): 92.

- Hou Lianbing and Luo Guixiang, “An outline of clinical new applications of Yunnan Baiyao in pediatrics,” Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1992; (5): 5–6.

- Ke Yan and Sui Chengzhi, “Yunnan Baiyao in treating hemoptysis of lung cancer,” Information on Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1990; (6): 35.

- Wen Yongjie, et al., “88 cases of infantile acute infectious stomatitis treated with Yunnan Baiyao,” Middle Journal of Medical Science, 1996; 31(4): 58–59.

- Wang Xiaoling and Wang He, “45 cases of anterior chamber bleeding treated with Yunnan Baiyao,” Jiangsu Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine, 1994; 15(7): 21.

- Lenaghan SC, et.al., Identification of nanofibers in the Chinese herbal medicine: Yunnan Baiyao, Journal of Biomedical Nanotechnology 2009; 5(5): 472–476.

- Tang ZL, et.al., Effects of the preoperative administration of Yunnan Baiyao capsules on intraoperative blood loss in bimaxillary orthognathic surgery, International Journal of Maxillofacial Surgery 2009; 38(3): 261–266.

- Tang ZL, et.al., Evaluation of Yunnan Baiyao capsules for reducing postoperative swelling after orthognathic surgery [in Chinese], Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2008; 88(33): 2339–2342.

- Li NC, et.al., The effect of Yunnan Baiyao on reduction of intra-operative bleeding of the patients undergoing transurethral resection of prostate [in Chinese], Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2007; 87(15): 1017–1020.

- Pan SF, Effects of Yunnan Baiyao on peri-operative bleeding of patients undergoing cervical open-door laminoplasty [in Chinese], Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi 2006; 86(27): 1888–1890. Chinese

Appendix: An Examination of Some Possible Ingredients of Yunnan Paiyao

While Panax notoginseng, known as sanqi, is usually indicated as a primary ingredient of Yunnan Paiyao, there is another, botanically unrelated, anti-hemorrhage herb, also called sanqi: Gynura japonica. It appears that Gynura was replaced by Panax notoginseng as the item labeled sanqi in the large herb markets since around the turn of the century. It is still a folk remedy in Southwest China. Gynura japonica (formerly, Gynura pinnatifida) was reported by Porter and Smith, in their 1910 publication (6), to be easily confused on the marketplace with Panax notoginseng (formerly Panax repens). In the Bencao Gang Mu, the description is that the herb was originally named “mountain varnish” (shanqi), later corrupted to sanqi (three-seven), and later to tianchi (farm seven), applied to Panax notoginseng, perhaps when it became a cultivated herb (the Wade-Giles spelling is tien-chi, and since it is a relative of ginseng, it is often labeled tien-chi ginseng). The name “mountain varnish” refers to the property of causing the edges of wounds to adhere together (and the fact that the herb was collected in the mountains). The herb was also termed jin bu huan, meaning gold is not as valuable; jin bu huan was a common name applied to many valuable herbs, not just this one, often assigned if they treated pain (7).

The Bencao Gang Mu also gives this description (for the botanical used as sanqi at the time it was written; mid-16th century): “The herb can stop bleeding, disperse blood stasis, relieve pain, and hence it is indicated for hematemesis, epistaxis, dysentery with bloody stool, profuse menstruation, retention of lochia, dizziness and pain due to blood stasis, acute conjunctivitis, carbuncle, and snake or animal bite. For wounds caused by sharp metal weapons and tools or flogging trauma, applying the powder or paste of the herb to the lesion can stop bleeding immediately (8).”

In the modern Illustrated Chinese Materia Medica (9), Gynura segetum is listed as sanqicao (same characters for sanqi as now used for Panax notoginseng; cao means weed, and this term is often applied when the whole plant or the plant top is used for medicine). Other Gynura species are used throughout S.E. Asia for many of the same applications as Yunnan Paiyao (10).

In recent packages of Yunnan Paiyao “liquor,” a formulation is given in Chinese characters and by transliterations or botanical identifications, as follows [comments are added in brackets]:

Sanqi (Panax notoginseng): 40% [could be other sanqi, namely gynura]Azuga forrestium: 17% [Chinese characters given are for sanyucao, “disperse stagnant blood weed”]Dioscorea opposita: 13% [characters read huaishanyao: dioscorea]Chuan Shan Long: 10% [the Chinese characters indicate chuanxinlong, “penetrate the heart dragon”]Lao Guan Cao: 7.2% [the Chinese character for guan is slightly off; “old crane weed”: geranium]Ku Liang Jiang: 6% [probably the same as galanga; “bitter” liangjiang]Bai Niu Dan: 5% [Inula cappa; Chinese name means white cow gall]Borneol: 1.5%

Musk: 0.3%

Sanyucao is also known as sanxuecao; it has been called “knife wound weed.” A species of Azuga is listed as one source of this herb. Sanxuecao is described as having the ability to control coughing, transform phlegm, clear heat, cool blood, eliminate swelling, resolve toxin; used to treat bronchitis, vomiting of blood, nose bleed, bloody dysentery, hematorrhea, swollen and painful throat, carbuncles, and external injuries. In the Bencao Shiyi, it says that “this herb primarily treats knife wounds and stops bleeding, promotes flesh growth, and stops nose bleeds (3).”

The label lists Dioscorea opposita as huaishanyao (the standard qi tonic herb dioscorea, produced in the Huaishan area), but dioscorea usually found on the market comes from other botanical species. Its relevance to the intended applications of the formula is unclear. Chuanshanlong usually refers to Dioscorea nipponica, which doesn’t grow in Yunnan Province. Chuanxinlong, as the Chinese characters read, is not to be found in the herbals, though there is chuanxinlien (same characters for chuanxin), which is andrographis. Since the term long (dragon) is used by alchemists to describe many herbs, it is possible that this is an old term for the herb (which is used for treating inflammation and bloody dysentery). There is another herb called chuanshanlong—Dioscorea althaeoides—which is a folk herb used to “dry damp, regulate the spleen, strengthen the tendons and invigorate the bones; it is recommended for wind-damp disorders, external injuries, and food stagnation.

The herb listed as laoguancao is most likely one of the several species of Geranium, though Erodium is sometimes substituted. Geranium is used to dispel wind, move blood, clear heat, and resolve toxin; it is indicated for wind-damp disorders, external injuries, cramping and numbness, sprain/strain, and numerous other health problems. The folk herbal of Guizhou specifically recommends it for external injuries accompanied by bleeding (3). Oriental Materia Medica (11) indicates it for rheumatism and trauma, among other disorders.

Kuliangjiang means “bitter galanga,” and it may be similar to the ordinary galanga, which is not produced in Yunnan. Galanga is used to treat pain and swelling (11). Bainiudan refers to Inula cappa (12), an herb that is reported to dispel wind, move qi and moisture, transform stagnation, and treat conditions such as pain and swelling.

Some insights into the contents and labeling can be obtained:

- The color of the powder is not white, as might be indicated by the product name. The color is the same as the capsule color used in the manufactured product, which is a dull pumpkin orange.

- The content of the capsule is not an extract, but a powder of crude herbs. If the powder is added to hot water and allowed to stand, one can see virtually clear water and particles of water-expanded powder that retains its original color. The powder form can maintain the microfibers.

- The dosage of Yunnan Paiyao used to treat bleeding and other disorders is substantially lower than the dosage of sanqi (Panax notoginseng), which is 1.0–3.0 grams each time, 3 times daily or 3.0–5.0 grams two times daily (total daily dose of at least 3.0 and up to 10.0 grams). Further, the amount of sanqi in the Yunnan Paiyao formula may be fairly small: at 40%, as indicated on the label for the liquor, it would correspond to ingesting only 100–200 mg sanqi each time the capsules are used. The main anti-hemorrhage ingredient of Panax notoginseng has been identified as dencichine (13).

- Overdoses of Yunnan Paiyao, with as little as 2.0–4.0 grams taken each time, were reported (14) to cause symptoms similar to aconitine poisoning. It was reported by one author (1) that a type of veratrum (pimacao) is an ingredient of the powder formula. The reported reaction could be due to one of the unidentified ingredients, such as veratrum, which contains powerful alkaloids. Several of the ingredients listed above would be unlikely to cause such a reaction at the dosage reported to be problematic.

- Many traditional patent formulas have labeling which differs from the actual constituents.